Event Date:

Conference on the Changing Nature of Family and Marriage in Contemporary Iran

To watch the presentations on Youtube, please click here.

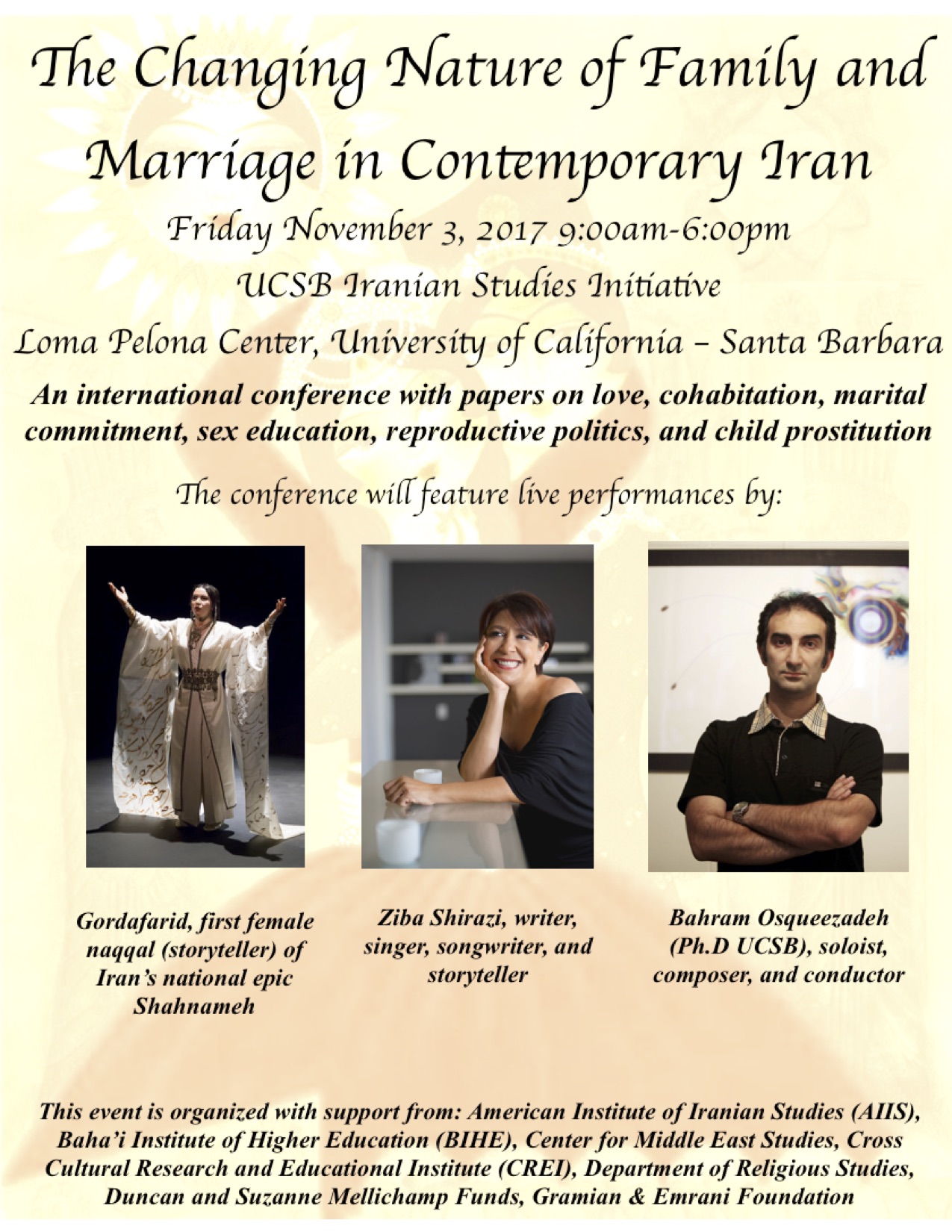

The Third Annual Conference of the Iranian Studies Initiative was held on Friday November 3, 2017. The event was convened by Janet Afary and Nicole Jafari, and organized by Jesilyn Faust (PhD Global Studies). Approximately 80 people joined us in dialogue and conversation related to our conference themes. This event was organized with the generous support from the Gramian-Emrani Foundation, which has made our annual conferences possible, as well as support from Duncan and Suzanne Mellichamp Funds, the American Institute of Iranian Studies (AIIS), the Baha’i Institute of Higher Education and Cross Cultural Research and Education Institute (CREI), the Dept. of Religious Studies, and the Center for Middle East Studies, UCSB.

Over the past few decades, Iran has experienced a dramatic change in courtship practices and in the institution of family. The Changing Nature of Family and Marriage in Contemporary Iran is a conference devoted to an exploration of the latest findings in this area. Papers will examine a variety of issues such as marriage and divorce laws vs. actually existing power and decision-making processes in the family, the role of the extended family, definitions of masculinity and femininity vs. the lived experience of individuals; gender disparity, variations in religious communities, family economics, especially unemployment, underemployment, female employment, and social justice. Papers will also look at the growing rates of street children (both Afghan and Iranian children) and child prostitution, the changing nature of temporary marriage, marital commitment, and cohabitation (white marriages).

Mary Hegland (Santa Clara University) gave the keynote address on her work in Aliabad, Iran, where she explored the themes of religion, ritual, politics, and gender. She observed that radical changes are taking place in rural and suburban areas of Iran, where marriages are becoming more about companionate and no longer strictly arranged. In 1978, marriage was inevitable and necessary in order to make the proper transition into adulthood. Marriage was seen as highly valuable, religiously essential, and beneficial, and the eventual marriage of one’s children was the apex of one’s life. However, by 2015, marriage had acquired less of a positive aura. It is also less inevitable. Not everyone marries and many delay marriage. Young people are questioning the institution and established rituals of marriage, such as when to marry, whom to marry, how long to stay married, or whether one should avoid marriage altogether. As women are becoming more educated than men, divorce rates have increased. With this shifting pattern, parents face a difficult situation: on the one hand, they feel obligated to pay for all the wedding expenses of their children. On the other hand, they are not as involved in the decision-making process as before. Young people care more about the influence of their peers than their family’s opinion when it comes to arranging a marriage and planning a wedding. The issue of women’s work after marriage and birth of children continues to be a daunting one. It is both a generational issue and gender issue. Mothers and mothers-in-law want to continue the pattern of the low urban employment of women (Iranian women participate even less than many other Middle Eastern countries in formal employment), while young women (though not necessarily their husbands) want a different lifestyle which they cannot easily attain because of high national unemployment.

Nicole Jafari (Cal State University, Long Beach) discussed the research of BIHE (Baha’i Institute of Higher Education) and how the grad students of this institute in Iran have used narrative therapy to explore a variety of subjects. BIHE is an underground university that educates Baha’i students who are not permitted to enter the university in Iran. Classes are taught by dedicated professors inside and outside Iran, sometimes through SKYPE. Graduate students undertake a number of research projects. One group of BIHE students has been studying Afghan and Iranian street children. Another group has been studying new parenting styles after the Iranian Revolution. A third group is studying extramarital relations, especially that of married women. A fourth group has been looking use of birth control methods. Since girls as young as 13 are increasingly becoming sexually active, many are relying on emergency contraception such as Plan B, which is easier to acquire, than birth control pills, which require a doctor’s prescription. Researchers in this group noted that Iranian teenagers have enormous misconceptions about sexual promiscuity in the US and Europe. Most believe that every single teenager outside Iran is sexually active. A fifth group of researchers is looking at urban professional women engaged in the formal labor sector to see if their greater economic power translates into greater say at home, compared to non-professional women. They concluded that professional women had some independent purchasing power but many hid their savings from their husbands. Also, while the women were contributed significantly to the household income, most had little say when it came to major purchasing decisions of the family, such as buying a home or a car. Unemployed women had even less authority in this area. Many were completely unaware of how much their husbands made and how he spent his income. The BIHE research group also organized sex education classes for parents and informed parents that children as young as 13 were becoming sexually active. Two thirds of the parents who went through the sex-education workshop found the information very helpful. However, a significant number of parents maintain that talking about sex with children will encourage them to engage in sexual activity.

Leila Salarpour Goodarzi (SUNY Binghamton) examined the relationship between mehr (an amount promised a woman at the time of her marriage to be paid upon death of the husband or dissolution of the marriage) and divorce. She explained that a wife’s unhappiness in marriage is not considered a valid reason for divorce in courts. Women often forfeit their mehr in order to receive their husband’s approval for divorce. A law passed in 2013 placed a cap on the amount of mehr a woman could request at the time of her marriage (110 gold coins, which is equal to $135,000 in today’s dollars). The results show that this change has reduced women’s bargaining power. Because the amount of mehr is arbitrarily low, and does not include community property, many unhappy women are staying in their marriages and not filing for divorce.

Behrouz Alikhani (Westphalian Wilhelms University – Münster) examined intertribal Bakhtiari marriages. Previously, members of the higher tribes would never consider marrying those from the lower tribal hierarchy. But today, educational achievements have somewhat broken down this segregation so that parents from higher tribes do consent to the marriage of their son or daughter with a member of a lower tribe, so long as that individual is highly educated and has great earning potential (a professor or a doctor). Thus, symbolic capital (status) is becoming less important vis-à-vis economic capital (degree and income).

Seyedeh Behnaz Hosseini (University of Vienna) looked at marriage among the Yarsani religious minority in western Iran. She argued that because of low birth rates and migration, more young people among the Yarsani are marrying outside their ethnic community or converting to Islam in order to marry members of the Muslim community, which creates new challenges for their community of origin and their opportunity to return to it in the case of divorce.

Ziba Jalali Naini (Shirazeh Publishing) discussed the phenomenon of White Marriages in Iran (sex and cohabitation without marriage). This type of relationship is different from muta’ (temporary marriage called sigheh in Iran), which is generally understood to be an arrangement between a wealthier/older married man and a poor, substantially younger woman. Instead, White Marriages involve the cohabitation of two consenting single adults of equal status. These relationships are taking place despite strict government prohibitions on cohabitation and extramarital sex. As the practice is becoming more prevalent in urban sectors, some liberal clerics have come up with appropriate religious explanations to justify these relationships, calling it mu’atat.

Maral Sahebjame (University of Washington) discussed the differences between White Marriage and temporary marriage. Muta’ (Sigheh) has a highly negative connotation in Iranian society, as the position of the woman is sometimes akin to prostitution. In contrast, most White Marriages are often second marriages for both partners and do not involve children. But White Marriages pose their own problems such as what to do if there are children in the relationship, or how to deal with infidelity in such a relationship, especially on the part of the woman. This has been a phenomenon that is still difficult to accept in the Iran’s highly patriarchal society.

Leila Zanouzi (UC Santa Barbara) Discussed Iran’s enactment of a progressive sex education campaign in the late 1980s. Premarital sex education became mandatory for both men and women. In these state-sponsored classes, respective couples were taught about reproductive issues as well as sexual pleasure. Today, Iran has joined the more industrialized nations of the world and fertility rates have dropped far below the replacement levels of 2.1. In 2013, the government reversed course and encouraged families to have more children. The previous successful sex education program was replaced with religious sexual instruction encouraging greater fertility. However, these efforts have not succeeded in increasing fertility rates. There has also been a great deal of resistance to this new trend by scholars and practitioners who argue that sex education should be taught as early as elementary school.

Shirin Gerami (University of Toronto) explored the government of Iran’s reactions to the increasing rate of divorce. The state has introduced six pilot programs to reduce divorce rates.

Shadi Sharifi (Toranj Project) discussed the epidemic rates of domestic violence in Iran. Approximately 60-70% of women have experienced at least one form of domestic violence in their lifetime. A group of young activists has produced an app to prevent domestic violence, which is similar to apps for campus sexual violence awareness in the United States. An individual can ask for help from friends and relatives in the case of domestic violence. The app, Toranj, has been downloaded 40,000 times. Information on this app can be found at: https://www.toranjapp.com/about-en.html.

In the final session of the conference Foojan Zaini (Personal Growth Institute) talked about what happens to married Iranian couples after they move to the United States and the challenges they face in their relationship, while Ari Babaknia (Chapman University), a medical doctor who pioneered some in-vitro fertilization techniques (IVF) talked about new possibilities for couples who delay having children.

In the evening, there was a reception at the residence at Gloria and Morris Sobhani’s residence, who graciously opened their home in Montecito to around 50 guests. The conference also included delightful performances by Gordafarid, Bahram Osqueezadeh (UCSB)and Ziba Shirazi.

The Fourth Annual Conference of the Iranian Studies Initiative will be held on October 19-20, 2018, and will be devoted to the subject of slavery and sexual labor in the Middle East and North Africa. There will also be an exhibit on display documenting slavery in Qajar Iran, organized by Pedram Khosronejad, Associate Director for Iranian and Persian Gulf Studies at Oklahoma State University.